If you’re an animal living through a mass extinction, it’s best to be one that’s found a unique way to make a living.

A new analysis of the species that lived or died out in the wake of the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs has revealed unexpected patterns that counter our prevailing theories of survival in the wake of mass extinctions.

A team of scientists with the University of Chicago, the Smithsonian Institution and the National History Museum of London carefully catalogued fossilized clams and mussels, assembling a picture of the ocean ecosystems just before and after the mass extinction 66 million years ago. They found that though three quarters of all species were lost, each ecological niche remained occupied—a statistically unlikely outcome.

“It’s a really interesting, and slightly disquieting finding,” said David Jablonski, the William R. Kenan, Jr., Distinguished Service Professor of Geophysical Sciences at UChicago and one of the authors on a new study published in Science Advances. “How ecosystems recover from mass extinctions is a huge question for the field at the moment, given that we’re pushing towards one right now.”

‘Extremely statistically unlikely’

In the history of Earth, we have documented five major extinctions—cataclysmic events in which the majority of species die out due to some worldwide change—and are currently edging towards the sixth mass extinction. Scientists are, therefore, very interested in understanding how biodiversity and ecosystems recover from these massive events.

Jablonski, along with paleobiologists Stewart Edie at the Smithsonian and Katie Collins at the Natural History Museum in London, decided to examine the most recent past extinction. Known as the end-Cretaceous, the event resulted in more than three-quarters of all known species dying out, including T-rexes and most of the dinosaurs.

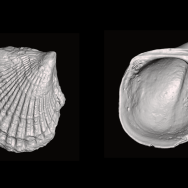

The team focused on clams, oysters, cockles and other ocean-dwelling mollusks. Their hard shells are abundant and fossilize easily, which was important because the team wanted to document as complete a picture as possible of the ecosystem—both before and after the extinction.

“What we wanted to do was not just count species, but count ways of life,” Edie explained. “How do they make their living? For example, some cement themselves to rocks; others tunnel into sand or mud; some are even carnivorous.”

The team painstakingly built a picture of the global ecological landscape just before the extinction, “before the roof came in,” Jablonski said, and compared it to the species found afterwards. And they got a surprise.